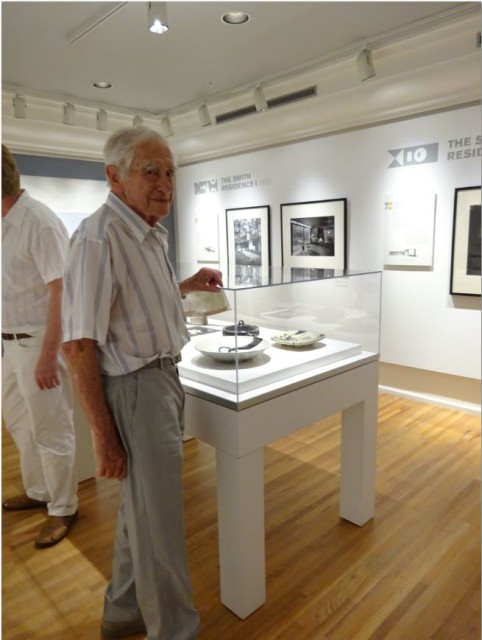

I finally got a chance to drop by the West Vancouver Museum yesterday to check out the latest exhibition on the photography of Selwyn Pullan. Assistant curator Kiriko Watanabe has done an amazing job, not only pulling out some of Selwyn’s most interesting work, but also displaying the cameras that he used to shoot them with.

I finally got a chance to drop by the West Vancouver Museum yesterday to check out the latest exhibition on the photography of Selwyn Pullan. Assistant curator Kiriko Watanabe has done an amazing job, not only pulling out some of Selwyn’s most interesting work, but also displaying the cameras that he used to shoot them with.

After serving in the Canadian Navy during the Second World War, Selwyn moved to Los Angeles to study photography at the Art Center School in Los Angeles where Ansel Adams taught. He worked as a news photographer at the Halifax Chronicle, and when he moved back to Vancouver in 1950 he found a new movement of artists and architects who were reinventing the house.

Selwyn reinvented architectural photography.

Several years ago, I asked him how he went about taking these photos. “I just look at the house and photograph it,” he said. “It’s a journalistic assignment not a photographic one.”

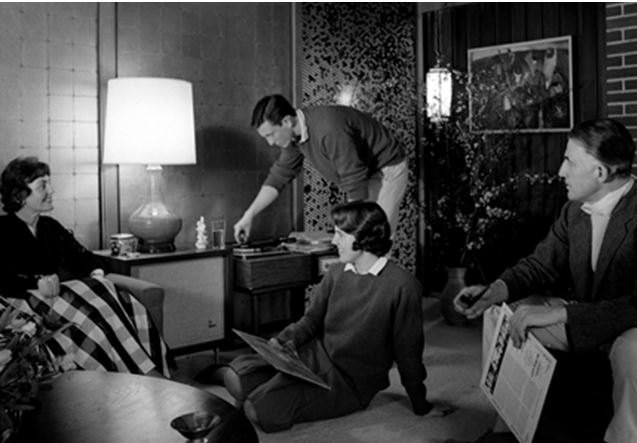

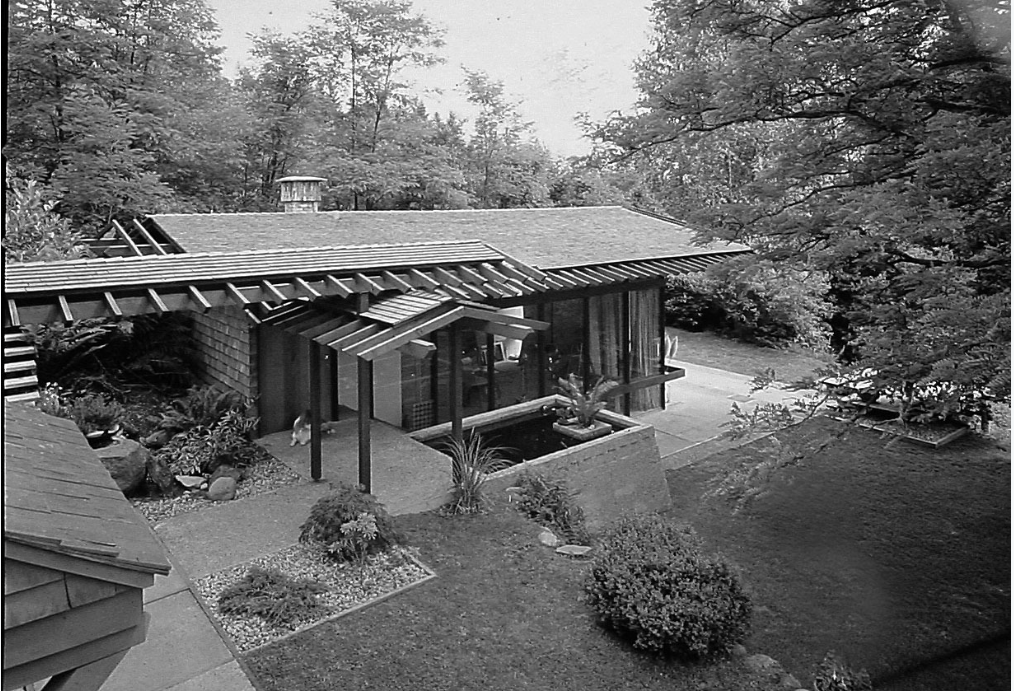

Many of his photos were taken in the 1950s and ‘60s. They evoke a sense of time, optimism for the future, and perhaps even a new way of thinking. He intuitively understood the work of the architects he photographed, emphasizing light and space and often pulling in the homeowners and their children to show how the architectural and interior design fit with family life.

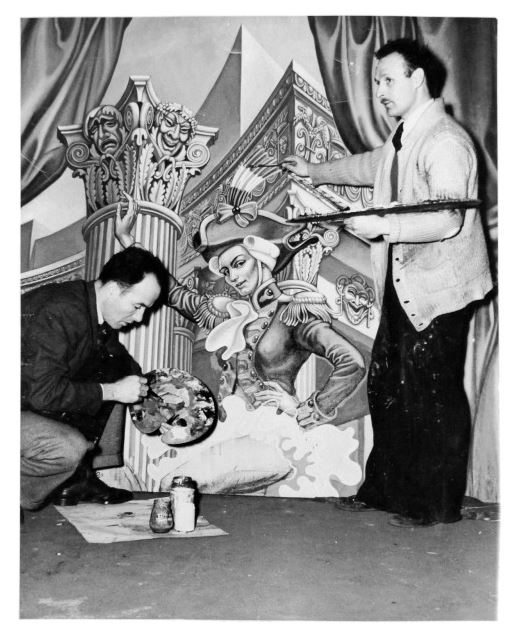

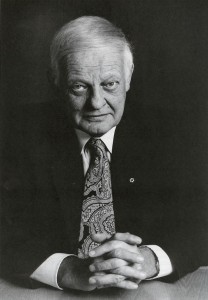

His pictures show Gordon Smith painting in the studio designed by Arthur Erickson; there’s a young Erickson lounging in his own adapted garage; and Jack Shadbolt is photographed painting in his Burnaby studio. His stunning portraits of artists and sculptors include E.J. Hughes, George Norris, Bill Reid and Roy Kiyooka.

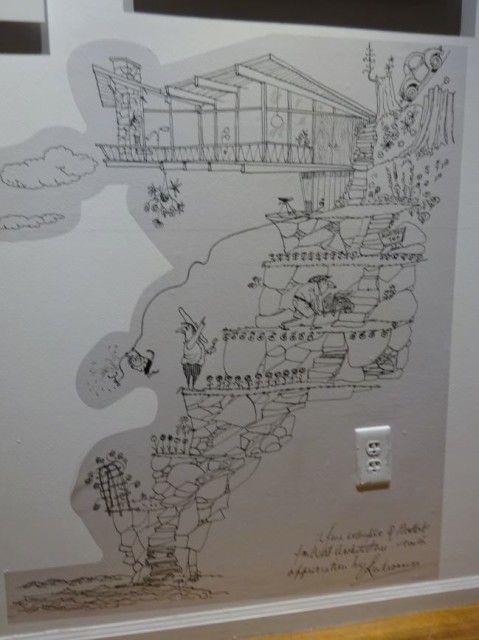

While the photos in the exhibition showcase Selwyn’s work, they are also carefully selected to show our missing heritage—building after building both residential and commercial that no longer exist. The loss is particularly apparent in West Coast Modern.

Go see this exhibition—it runs until July 14. There’s a guest talk by Donald Luxton on Saturday June 30 at 2:00 p.m. which will be well worth your time.

Selwyn died last September, after spending 65 years in his North Vancouver house, where he worked in his Fred Hollingsworth-designed studio, and where he parked his jaguar under a Hollingsworth-designed carport.

Top photo caption: Birks Building. Architect Somervell and Putnam. Built 1912, demolished 1974.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.