Mountain View Cemetery may have been Vancouver’s first official cemetery when it opened in 1886, but Stanley Park was first.

Bodies had been buried on Deadman’s Island in Coal Harbour for thousands of years, and those who didn’t want their relatives interred alongside the socially undesirable, the diseased or unchristened, moved their burials further into Stanley Park.

This story is from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

The Pioneer Cemetery:

“Its very association with the First Nations and Chinese immigrants thus designated Deadman’s Island as a resting place for the pagan, the unchristened, and the socially and culturally anathematized,” says local historian Maurice Guibord.

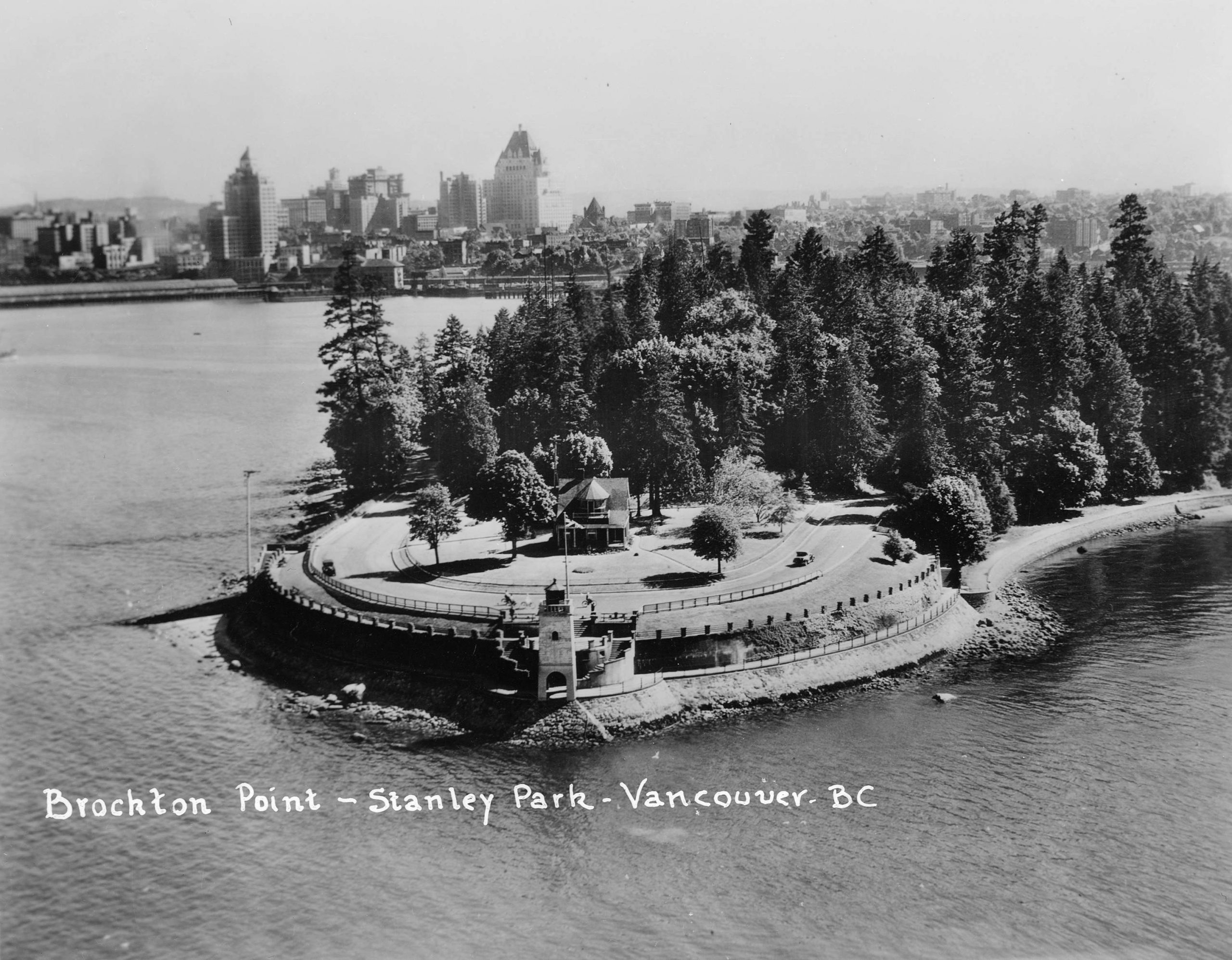

The stretch of land from Brockton Point Lighthouse to the Nine O’Clock Gun had always been a burial ground for the Indigenous people who lived there, but as Gastown was settled it also became an alternative burial ground known as the Pioneer Cemetery.

Chinese burials:

Chinese people were initially buried there, but for most, it was only temporarily. The custom was to return the bones to China eventually, so the graves were shallow to allow for faster decomposition and to facilitate exhumation. Once the body had turned to bones, they were dug up by bone collectors, cleaned, packaged and returned to China. Failure to do this was said to create po—homeless and malevolent ghosts who stuck around and haunted living relatives.

Maurice believes that there are up to 200 bodies still buried there along the peninsula, including the remains of settlers, some Chinese people and the indigenous people who had abandoned the custom of above-ground burials.

Unmarked graves:

The graves weren’t officially marked and the burials weren’t recorded, so when the perimeter road was built around the park in the late 1880s, the bodies were just paved over. “They are buried under the road, under the trees, under the bike path and the walkway. They are all through there,” says Maurice.

Something to think about the next time you’re sitting in the car park or taking a walk along the Seawall.

For more ghostly stories check out these podcast episodes:

S1 E9 Three Ghost Stories and a Murder

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

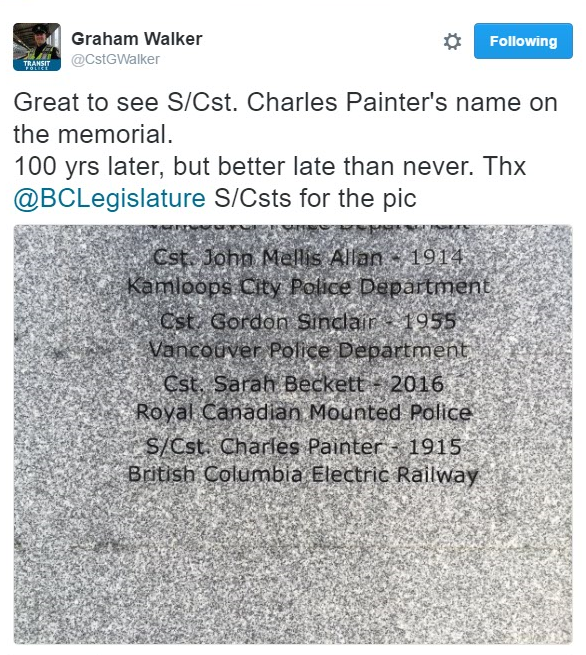

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.

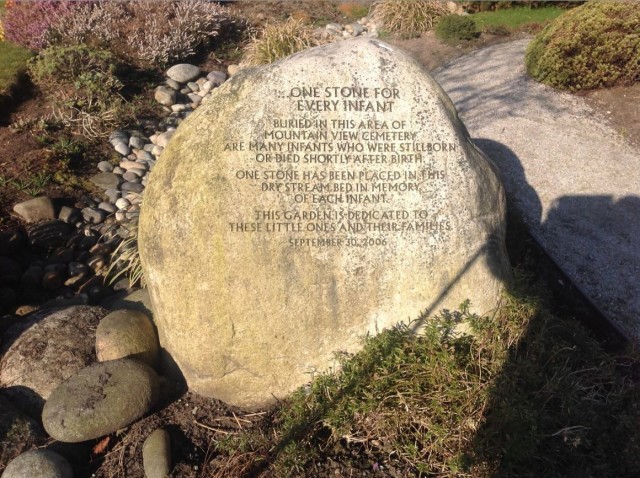

The garden is just a short walk from the main office, chosen because that particular piece of ground was once known as Block 18, the biggest of the mass graves.

The garden is just a short walk from the main office, chosen because that particular piece of ground was once known as Block 18, the biggest of the mass graves.