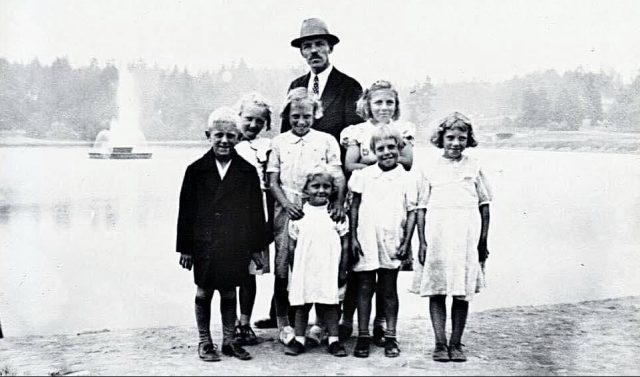

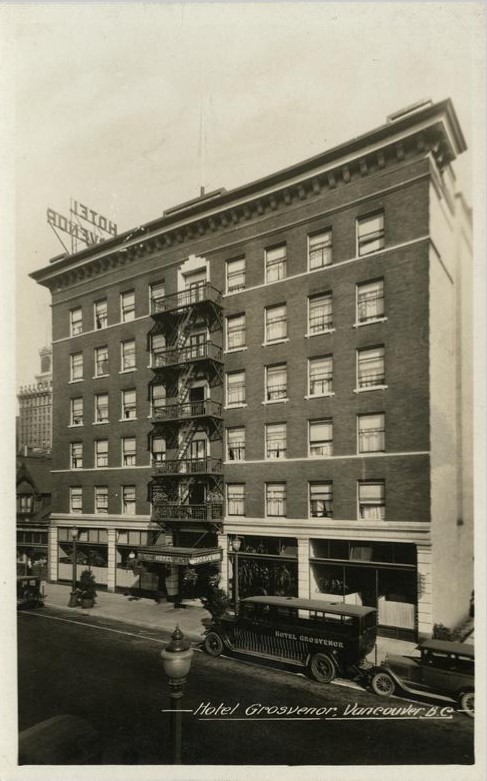

In December 1989, Ramsey Rioux and Kenneth Lutz were two indigenous 13-year-olds living in North Burnaby, BC with Ramsey’s uncle and his family. Ken had previously lived with his father in the West End, and even though things weren’t going well, he was having trouble adjusting to a new school, new family, new friends and a different neighbourhood.

He would often take Ramsey and head back to the West End.

So, when they went missing, police immediately categorized them as prolific runaways, and it doesn’t appear that they looked too hard to find them.

Both boys were five foot three with dark hair and brown eyes. Ken had a slim build and a scar over his left eye. On the day they went missing they were dressed almost identically in denim jackets with wool collars, black jeans and white runners.

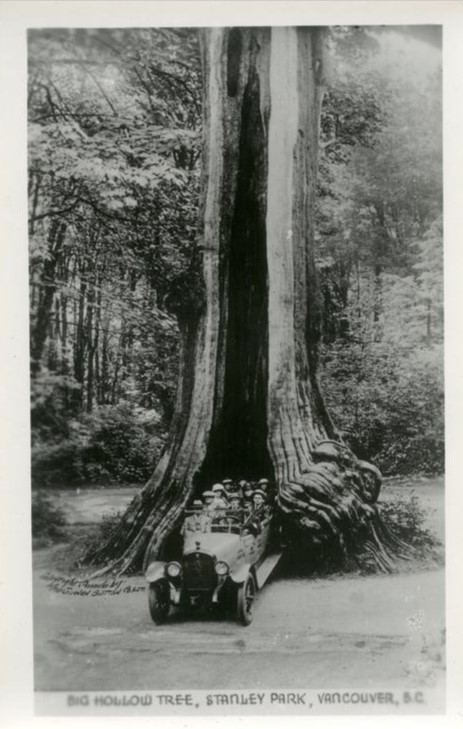

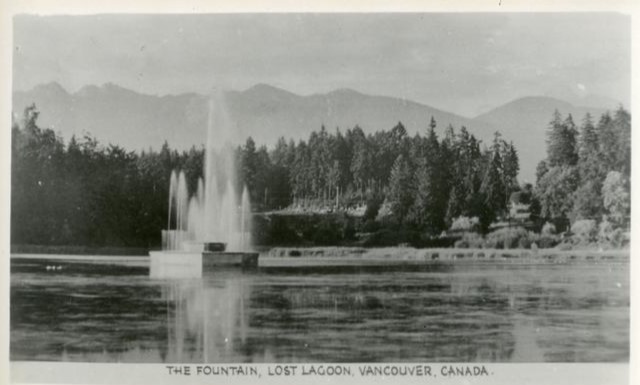

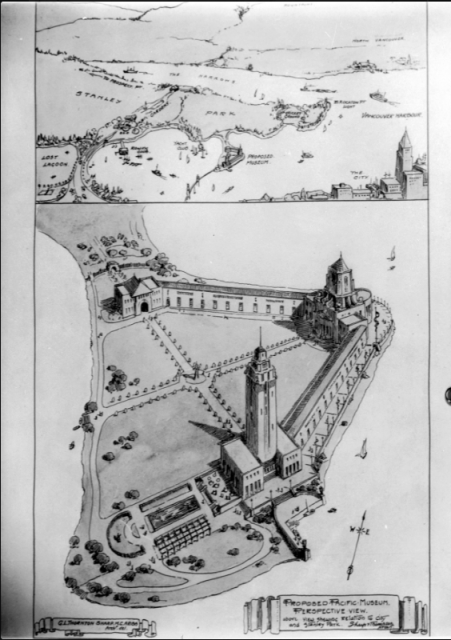

Skull discovered in Stanley Park

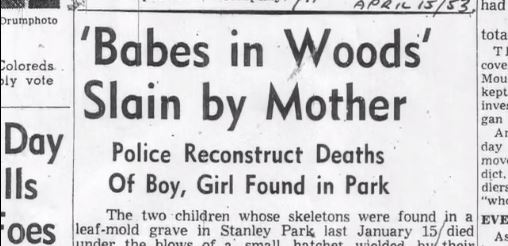

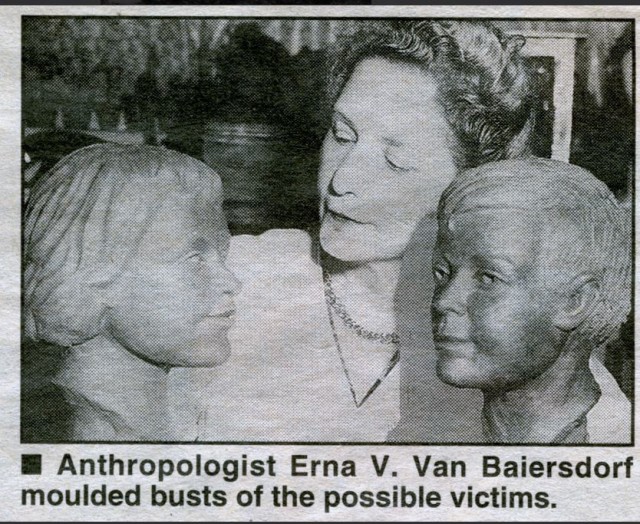

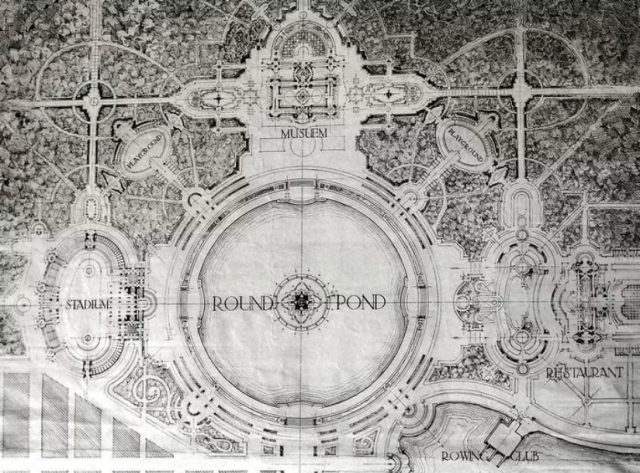

In the summer of 1990 a hiker discovered a skull near Beaver Lake in Stanley Park. The skull had good quality dental work which ruled out the possibility that it came from an Indigenous burial ground. The coroner’s office created a composite image using bone and teeth structure. It was determined that the skull belonged to an indigenous or Asian girl aged between 14 and 16.

In 1998, the case of the unidentified skull in Stanley Park came across the desk of detective Al Cattley of the newly formed Provincial Unsolved Homicide Unit. After the mix up of genders in the Babes in the Woods case, Cattley wondered if the skull had also been misidentified. He had the skull tested for a DNA, and found that the skull belonged to a teenage boy.

Police from the cold case unit searched through missing persons reports and eventually narrowed the search to Ramsey Rioux and Kenneth Lutz.

Second Search produces tips

Stanley Park was searched again, but nothing was found that could be linked to the two boys.

Publicity generated by the search—including a segment on America’s Most Wanted—produced some promising tips from the public.

Corrinna saw the show. She was Ken’s 13-year-old girlfriend and probably the last person to see the boys in Burnaby on the day that they disappeared. She called the tip line, but was told it was okay they didn’t need to speak with her. If they had taken the time to interview her, they would have found out a lot of potentially useful information.

The boys dropped by her house and told her they were running away to Saskatchewan and dropped off a Christmas present for her. She said they didn’t have any money and only a few clothes in their backpacks.

Skull Found:

In 1995, A West End resident was foraging for wood in Stanley Park when he saw a skull in the bush. He took it home and popped it on a shelf in his basement. The skull stayed there for the next three years. Eventually he handed over his find to police and took Cattley to the spot where he had found it. Cattley was surprised to discover that it had been located just 60 metres from where Ramsey’s skull was discovered in 1990.

Cattley thought the boys may have been victims of a pedophile ring that operated in BC in the 1970s and ‘80s. This was never confirmed and no other parts of the boys bodies were ever found.

Ramsey Rioux is buried at the Fairview Cemetery in Prince Rupert, BC. Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to find out where Ken Lutz is buried.

Show Notes:

Music: Andreas Schuld ‘Waiting for You’

Intro and voiceover: Mark Dunn

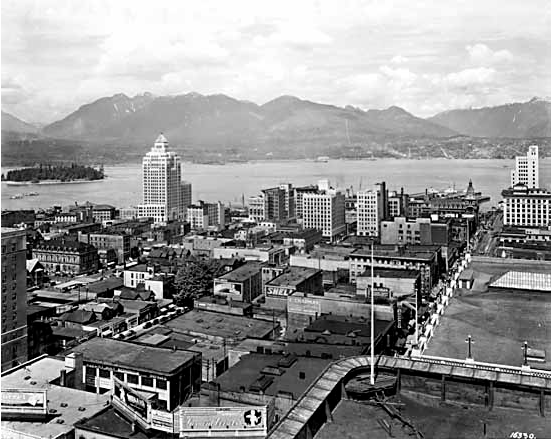

With thanks to Aaron Chapman, author of Vancouver Vice for his insights into Vancouver’s West End in the 1980s

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.