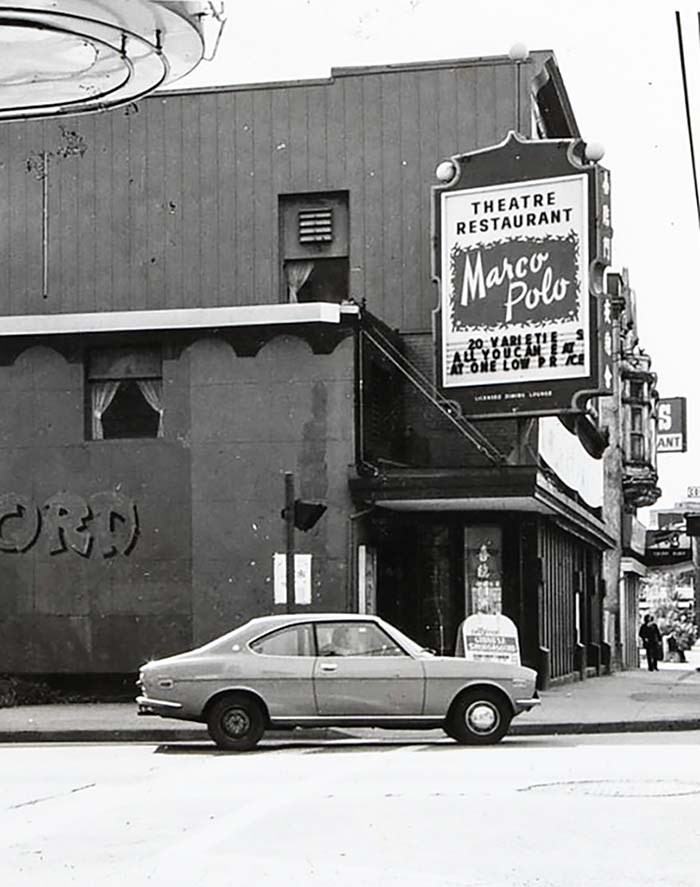

Long before the Vancouver Film School occupied the building at East Pender and Columbia Streets, there was a railway station that was later repurposed into the legendary Marco Polo restaurant.

Story from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

Train Station:

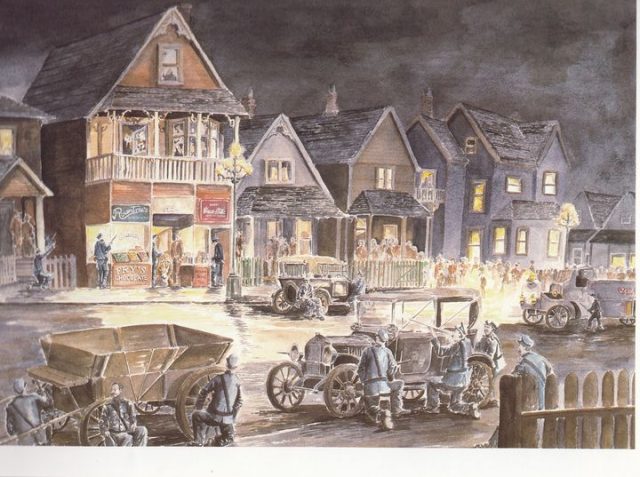

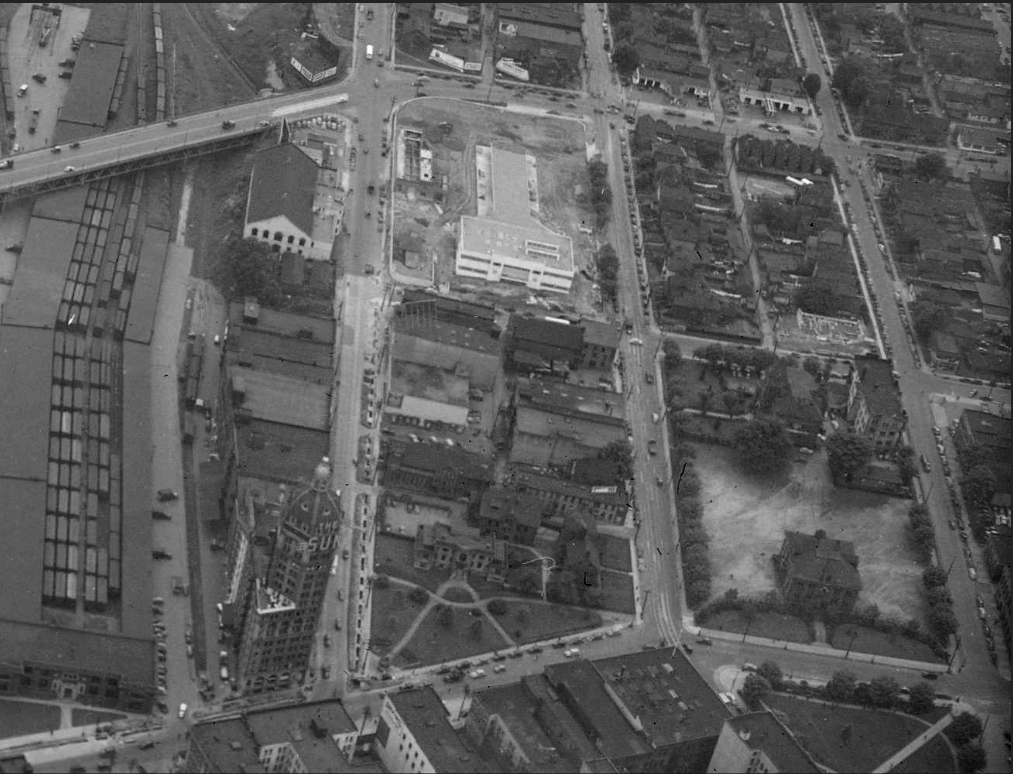

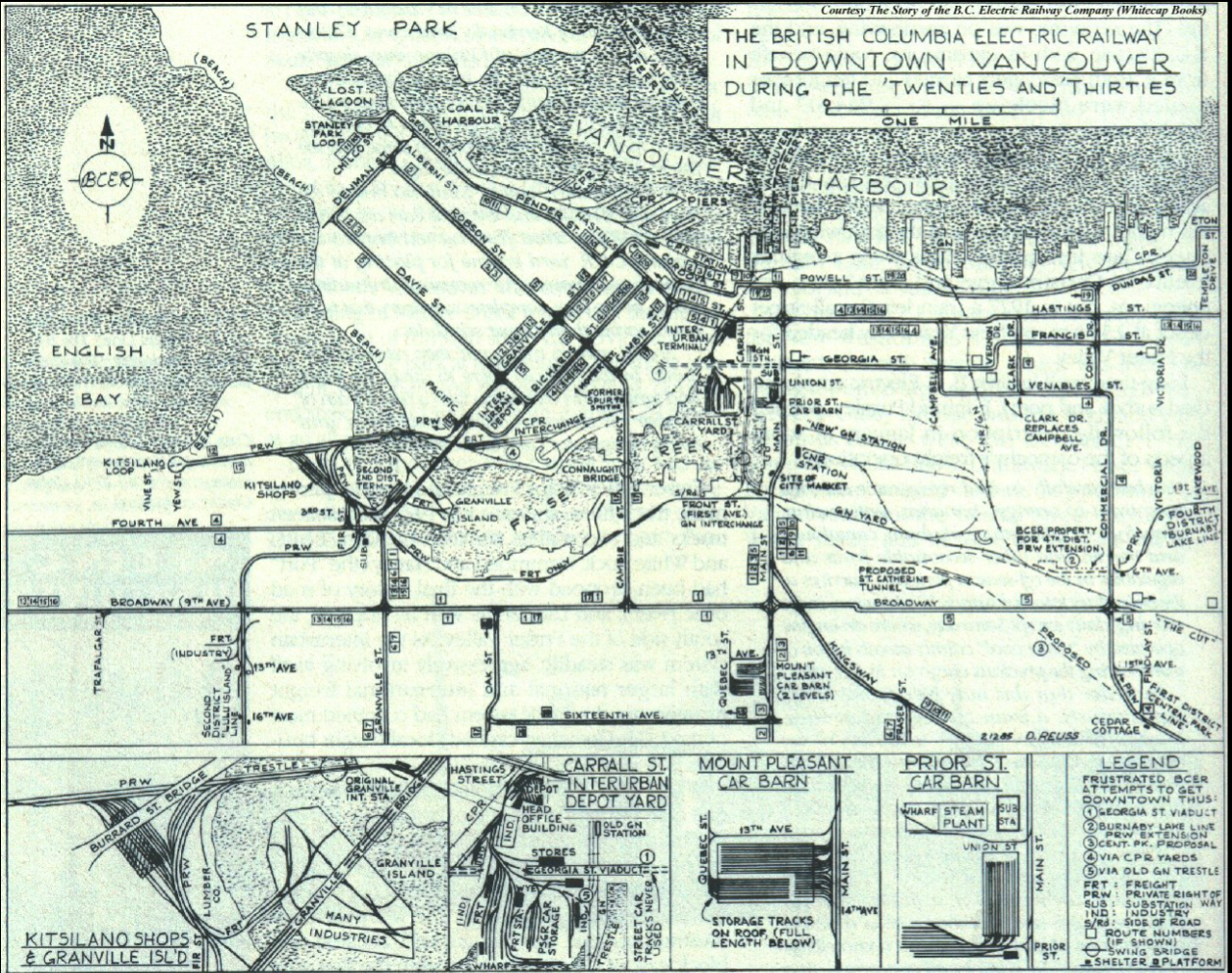

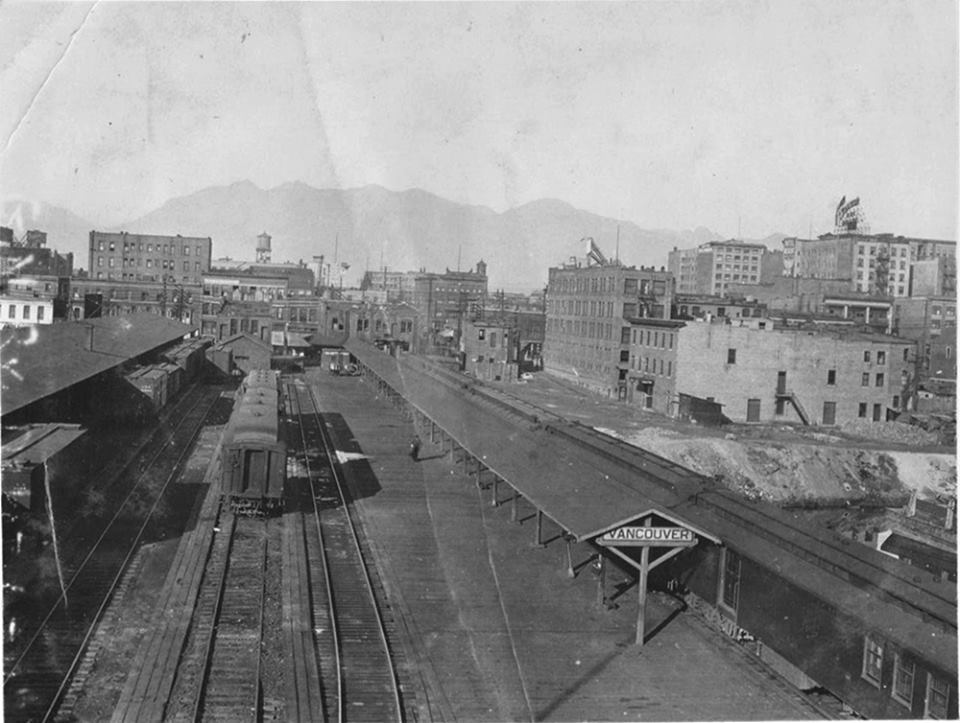

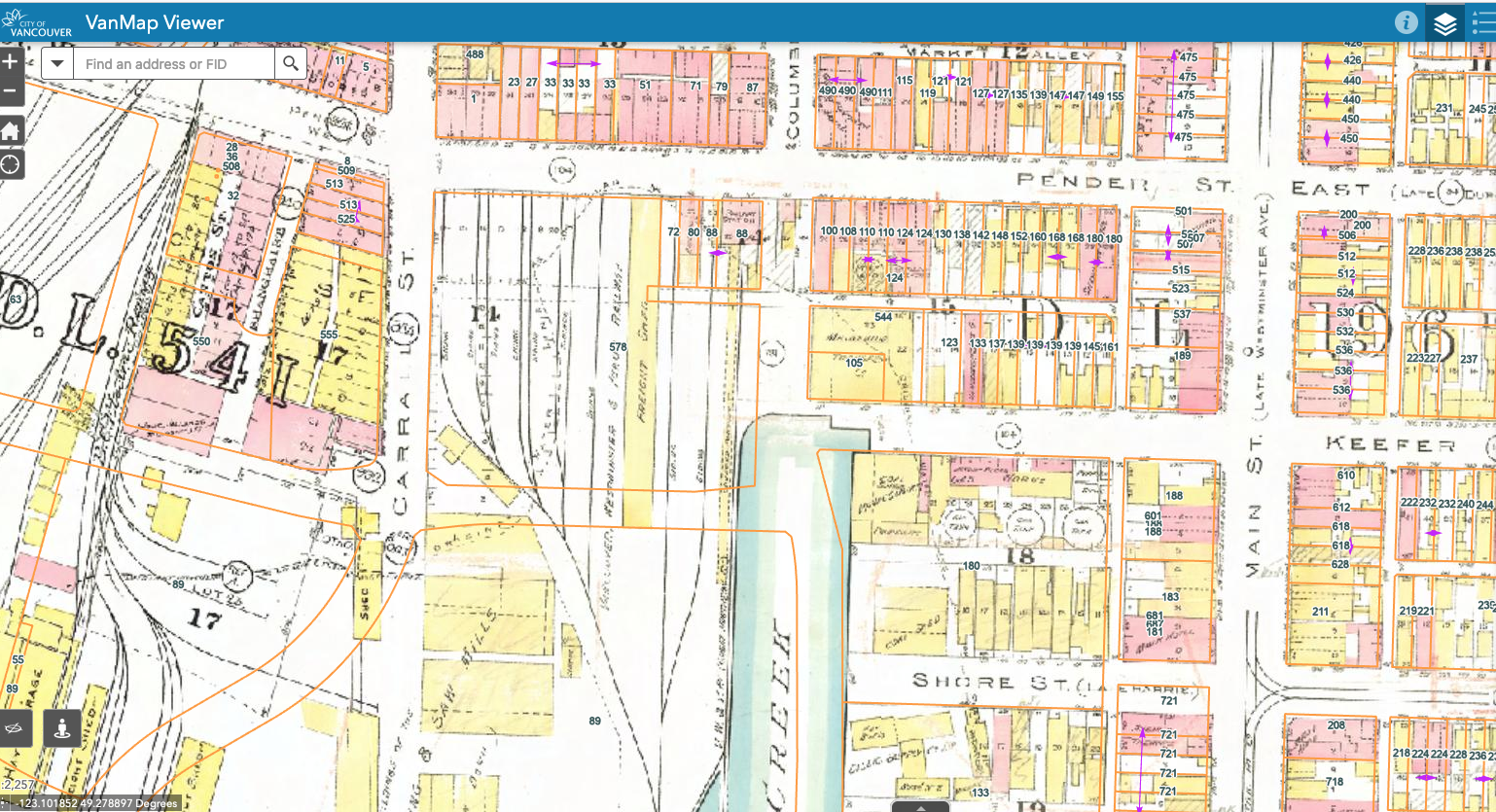

If you’re walking around Chinatown, you’ll likely notice the four-storey brick building at the corner of East Pender and Columbia Streets, now home to the Vancouver Film School. But if you were to take a stroll down the 100 block of East Pender in the early years of the 20th Century, you would actually be on busy Dupont Street and you’d find visitors from the U.S. disembarking at the Vancouver, Westminster and Yukon Rail depot.

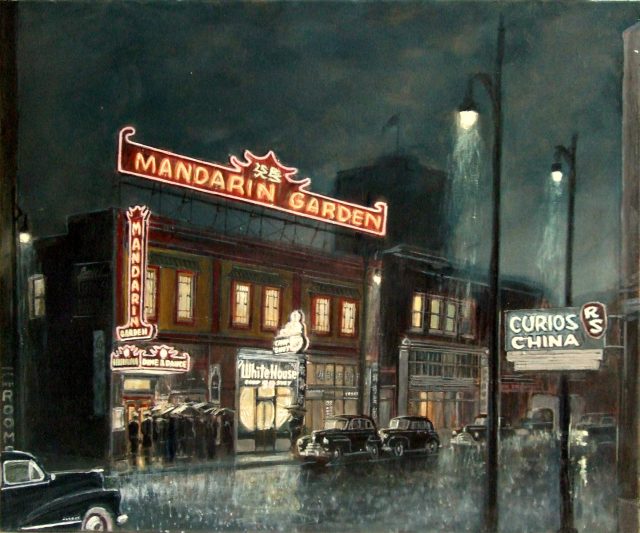

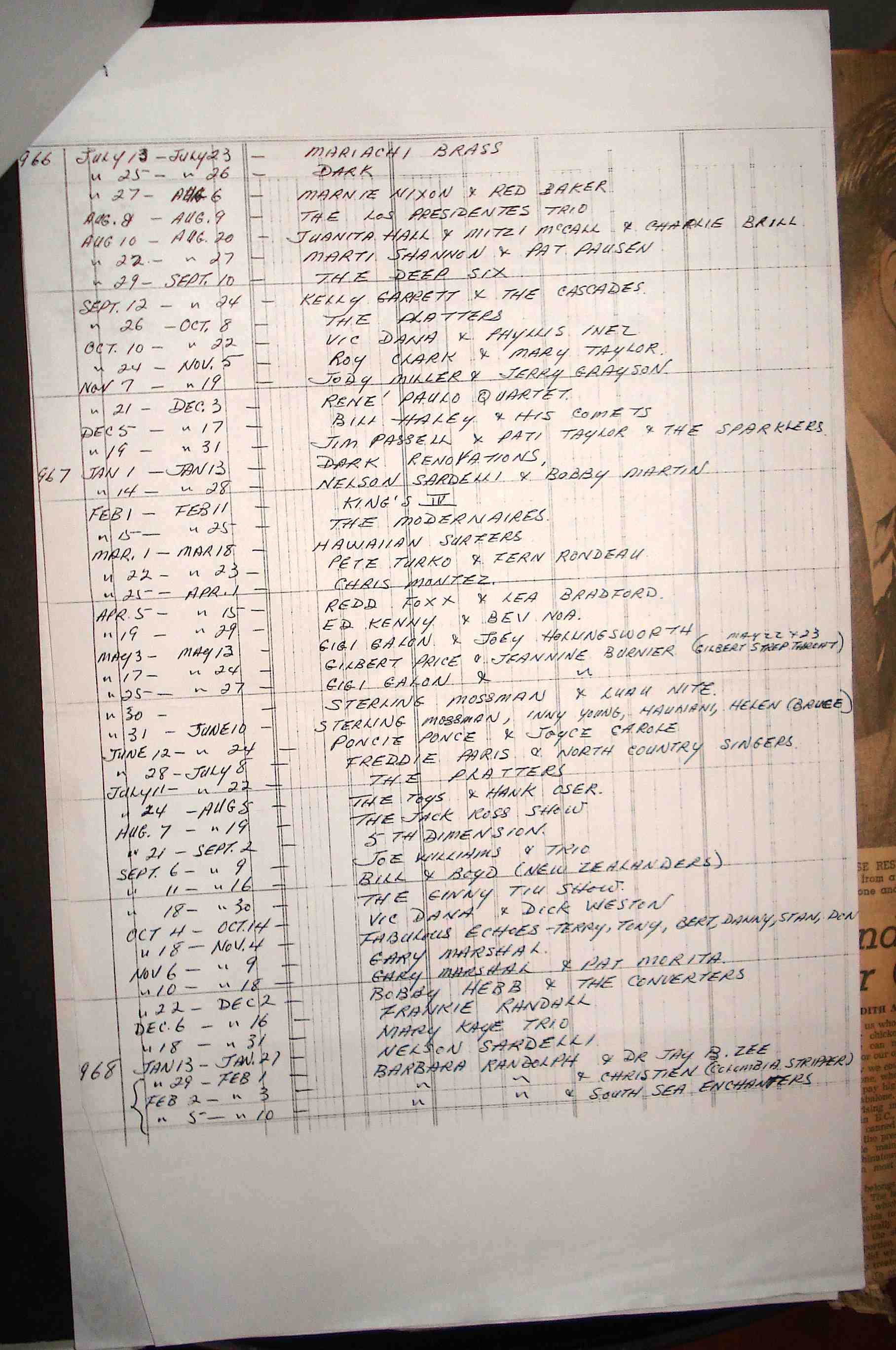

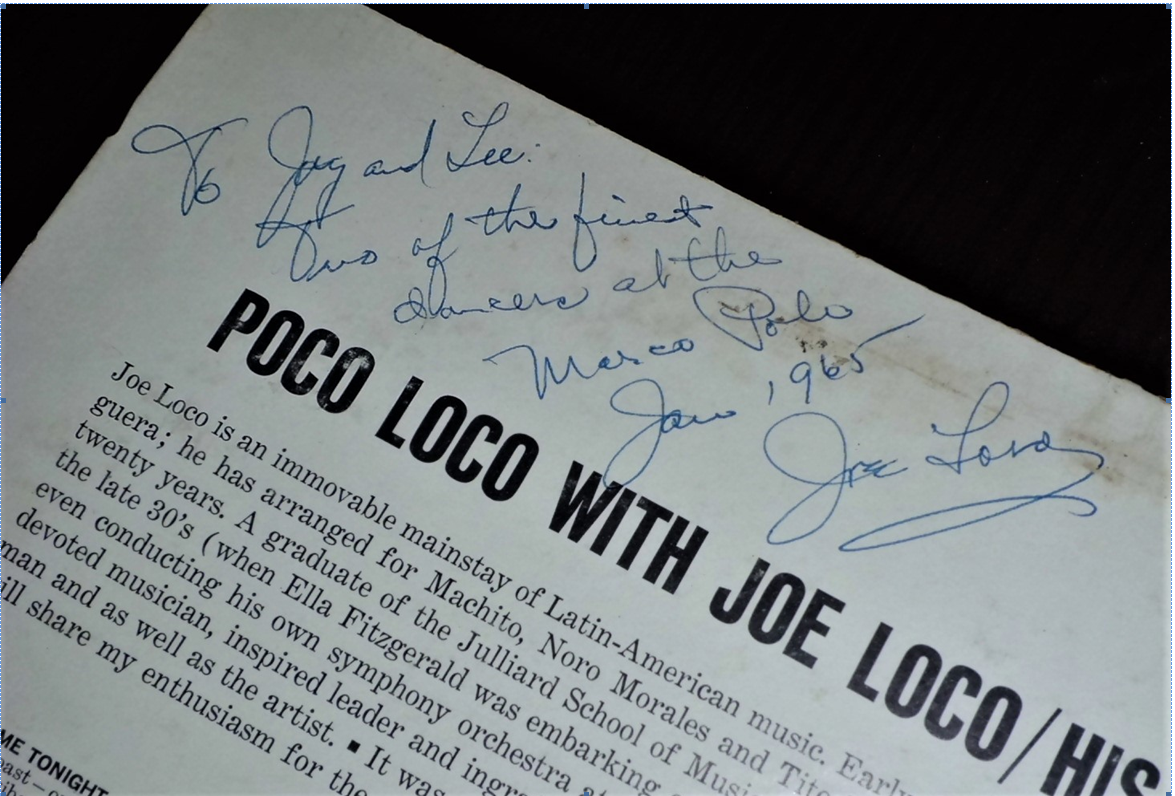

Several hundred people came to see the first fast train leave for Seattle on March 20, 1905 and cross the new trestle bridge that connected the north and south sides of False Creek. The last train left on May 31, 1917 and the building turned into the Hu Ye Restaurant and later the Forbidden City. The last and most famous tenant was the Marco Polo Restaurant.

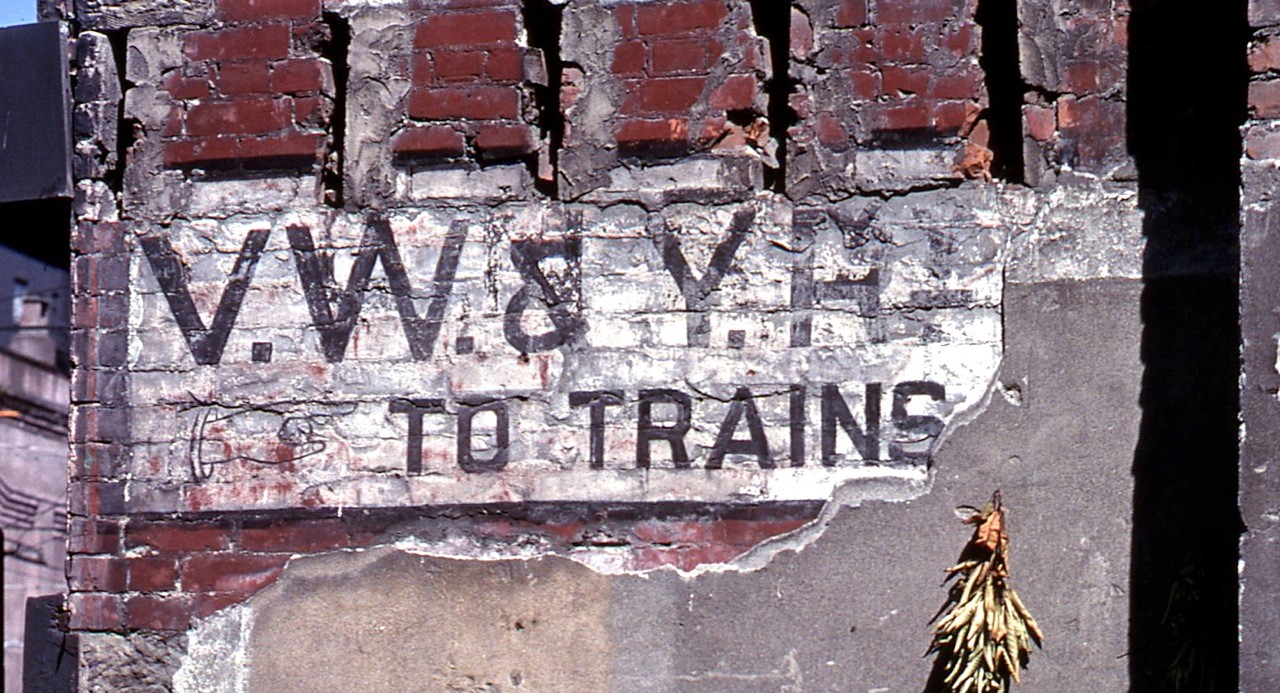

The Ghost Sign:

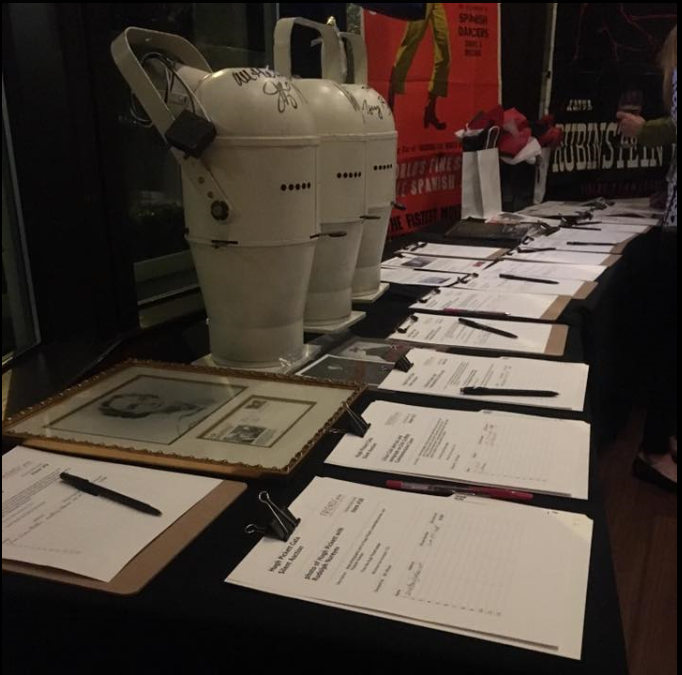

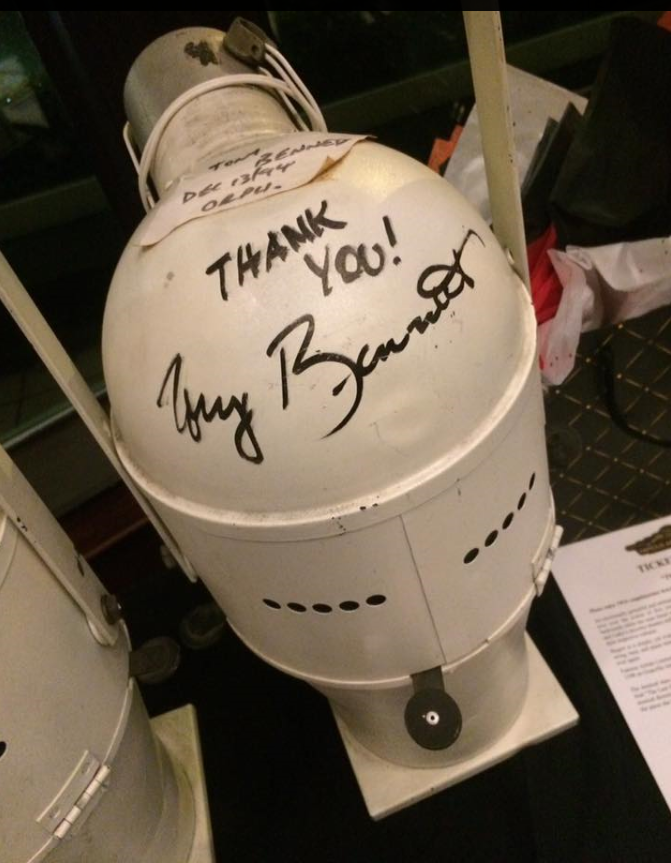

Before the building could be destroyed in 1983, heritage advocate Arthur Irving made a deal with the demolition crew and pried 88 bricks off the wall that still had the original railway sign VW&Y To Trains printed in black letters. He had the bricks mounted in a box to preserve them, and in doing so, saved one of the few pieces that remain of the Vancouver Westminster and Yukon Railway that operated between 1904 and 1908.

After Arthur died in 2018, Tom was helping to clear out his house when he came across the sign and the blueprints for the Great Northern Station built in 1919. “We found them in Arthur’s basement, in a bathtub salvaged from the 1916 Hotel Vancouver,” says Tom.

The brick sign and the blueprints are with the West Coast Railway Association in Squamish. The bathtub is in Arthur’s next-door neighbour’s garden.

© Eve Lazarus, 2022

Related: