In May 2014, the City of North Vancouver inked a deal with the Squamish Nation and moved a step closer to realizing the dream of building a 35-kilometre waterfront trail that would wind its way from Deep Cove to Horseshoe Bay. The mostly finished portion of the Spirit Trail runs from Sunrise Park (just above Park and Tilford Gardens) to 18th Street in West Vancouver–(just past John Lawson Park). The ride (or walk) along the finished portion is about 20 km return.

The Moodyville Park section was completed in 2015. The trail includes an impressive overpass to Heywood Street, a mini-suspension bridge, public art, and some now fading public markers. You’ll have to reach deep down into your imagination, because the only thing left of Moodyville is a small park with some signage surrounded by a lot of building activity.

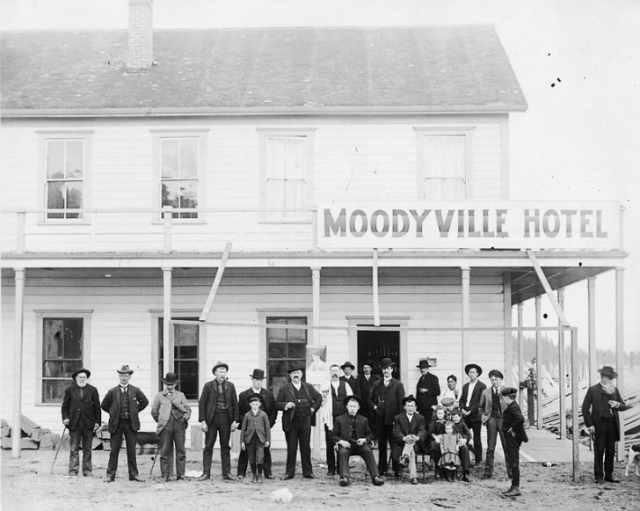

Up you go over the new overpass, and a great view of the working waterfront that takes you right into Moodyville, once a thriving town built entirely around lumber. Settled in the early 1860s, the town was completely distinct from the rest of North Vancouver with a business district that included a library, Masonic lodge, school, jail and cookhouse situated where the railway tracks and grain elevators are today. The mill was at the foot of what is now Moody Avenue, and a wooden wharf extended from the mill out over deep water. The town even had its own ferry service.

While the workers were comprised of several different races who could trace their origins back to Europe, Asia, the Pacific Islands “Kanakas,” Latin America and the West Indies, lived in segregated housing; the wealthy lived in “Nob Hill” a nod to San Francisco’s prestigious neighbourhood.

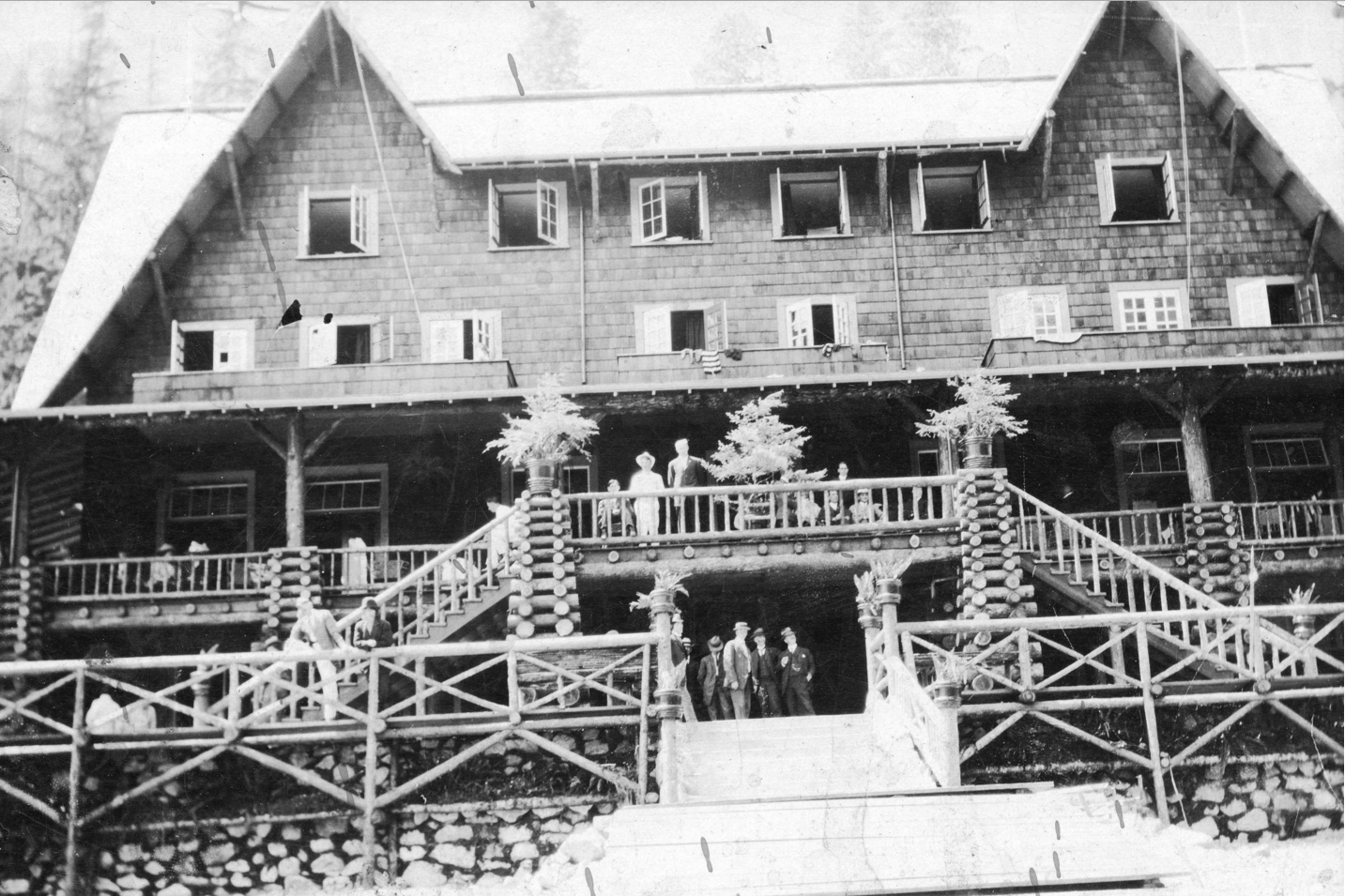

The most prestigious house was Invermere, known as the “Big House” and built in the late 1870s for Hugh Nelson a partner in the Moodyville Sawmill Company (later Lieutenant Governor of BC). Lumberman John Hendry bought Invermere and lived there for a time. His son-in-law Eric Hamber, another Lieutenant Governor of BC, demolished the house after his death. The replacement house is at 543 East 1st Street.

Electricity came to Moodyville in 1882, a full five years before Vancouver and the electric lights reflected all the way across the waters to Hastings Mill in Vancouver. Moodyville was the first town site north of San Francisco to sport electric street lights.

By 1898 the Mill’s fortunes had peaked and in 1901 it closed. People moved away in search of work, and business activity shifted to the waterfront at the foot of Lonsdale Avenue. Moodyville officially became part of North Vancouver in 1925.

The Low Level Road, constructed two years later, paralleled the railway line. Much of the hillside was scraped away and re-deposited as fill on the tidal flats to reclaim 15 acres (6 hectares). Midland Pacific was first to locate on the fill and opened a grain elevator in 1928. The area known as Nob Hill was subdivided, war-time housing followed, and a housing development called Ridgeway Place sold in the late 1950s.

With thanks to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives for letting me work on their Water’s Edge Exhibit in 2016.

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

Pemberton to Capilano River (part 6)

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.