Since I write about history and cold cases, it’s not often I’ve get to break an actual news story. But thanks to a young woman named Ally who went searching for her Great Uncles—I can now tell you the names of the Babes in the Woods—the little boys whose skeletons were found in Stanley Park in 1953. Meet Derek and David D’Alton.

This episode is based on a chapter in my book Cold Case BC: the stories behind the province’s most sensational murders and missing persons cases

When Ally spit into a tube in 2020, she had no idea that her DNA would help to solve one of Vancouver’s oldest and coldest murder mysteries.

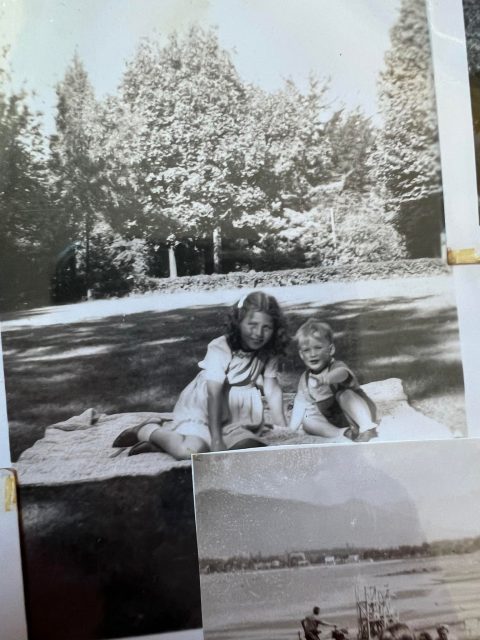

Ally was flicking through the family album one day when she discovered that she had two great uncles who she had never met. The older boy had blonde hair and blue eyes, and the younger had darker features. When Ally asked her grandmother Diane who they were, she found out they were Diane’s younger brothers David and Derek.

Taken by social services:

Twenty-six year old Ally, says the story handed down in the family was that the two little boys were taken away by social services because their mother Eileen who was of Metis heritage, was too poor to look after them. Diane remained with her mother. “I remember my mother sharing stories with me about her mother’s poverty and how they used to jump out of windows at places they were renting in Vancouver to avoid having to pay because they were just so poor,” says Ally.

But when Ally’s Mum Cindy pressed her mother Diane for more information, Diane would tell her: “we don’t talk about that” or “that’s in the past.”

Genetic Genealogy:

Cindy wanted to find out her mother’s genetic mix, so she took a swab from Diane, who was by then suffering from dementia, and sent it off to MyHeritage. Then Ally spit in a tube and sent it to 23AndMe—a genealogy database where people go to learn about their ancestry and locate lost relatives. She hoped to find her great uncles still alive, or at least trace their children or grandchildren.

Ally didn’t have the boy’s birth certificates or know the year they disappeared, but she knew that Diane was born in July 1937 and was the oldest and then came Derek and David. All three children attended Henry Hudson Elementary in Kitsilano.

Ally uploaded her DNA to Ancestry, MyHeritage and several other genealogy platforms. She hoped her DNA would lead her to her great uncles, instead, what she found was devastating.

Identified:

Last May, the Vancouver Police Department partnered with the BC Coroners Service and a Massachusetts-based forensic research firm, to try and identify the Babes in the Woods. Most of their remains had been cremated in the 1990s and only a few fragments were left. These tiny, very old and fragile bone fragments were sent to Lakehead University’s Paleo-DNA lab in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The lab successfully extracted DNA from the bone fragment of the older boy and sent that to a lab in Alabama for DNA genome sequencing. His DNA kit was uploaded to GEDmatch, and a team of forensic genetic genealogists began searching for living relatives.

Then, earlier this month, Cindy was approached by a VPD detective who told her that her uncles were the two skeletons that had been found in Stanley Park in 1953 and who were known for the next seven decades as the Babes in the Woods.

Their mother, Eileen Bousquet was born in Alberta, and as far as Cindy is aware all three of her children—Diane, Derek and David were born in Vancouver. Detectives told Cindy that they hadn’t found any records to indicate that the boys were taken into the custody of child protection services as she had been told, but they would continue searching.

Killed by mother?

Police have always believed that the boys were killed by their mother, who covered them up with her coat. But Cindy doesn’t believe that for a second. She says her grandmother was a lovely, gentle woman. “She was a huge animal lover, she babysat little kids. She was very sad because something had happened and I don’t know what it was because nobody wanted to talk about it.”

Eileen died in 1996 at age 78.

Ally says her grandmother Diane didn’t know who her father was or who the fathers were of her half-brothers. “That’s something I’ve been trying to trace with Ancestry, but so far no luck,” she says. “Even though it came to a devastating resolution, at least we know what happened.”

- The VPD have released the boys names as Derek (born Feb 27, 1940) and David D’Alton (born June 24, 1941). The police believe they were murdered in 1947 so Derek would have been 7 and David 6 when they were killed.

- All photos courtesy Ally

Show Notes

Sponsors: Forbidden Vancouver Walking Tours

Music: Andreas Schuld ‘Waiting for You’

Intro : Mark Dunn

Sources:

News report courtesy CTV Vancouver

Huge thanks to Miles Steininger, Darlene Ruckle, and The History Five for all their help with the research

Related stories:

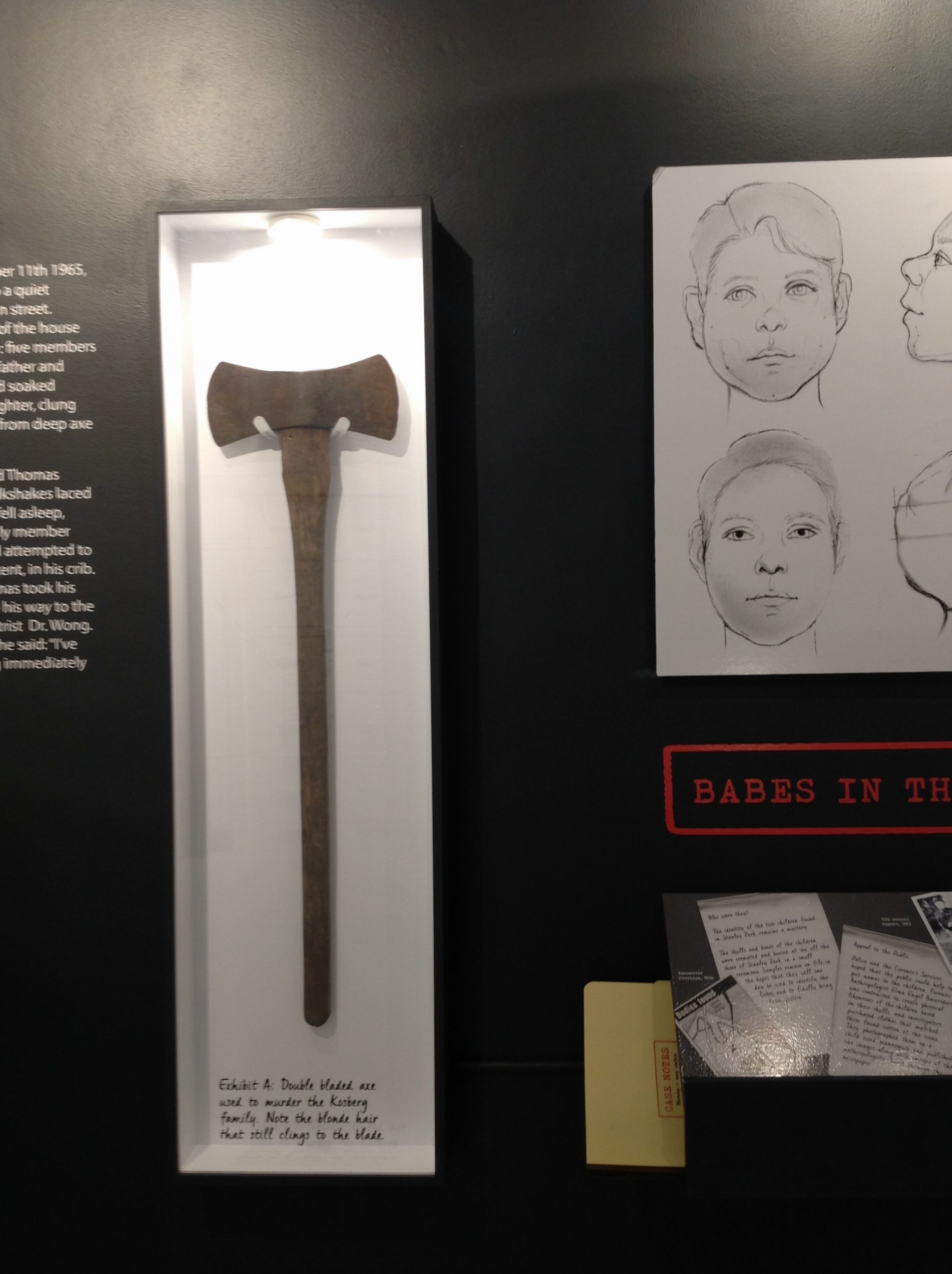

- The Babes in the Woods Part 1 – Season 1, Cold Case Canada

- The Babes in the Woods Part 2 – Season 1, Cold Case Canada

- Cold Case Vancouver: The City’s Most Baffling Unsolved Murders

- McCarter: the 20-year-old from Alabama who got the Babes in the Woods Case

- Vancouver Sun February 15, 2022

© Eve Lazarus, 2022

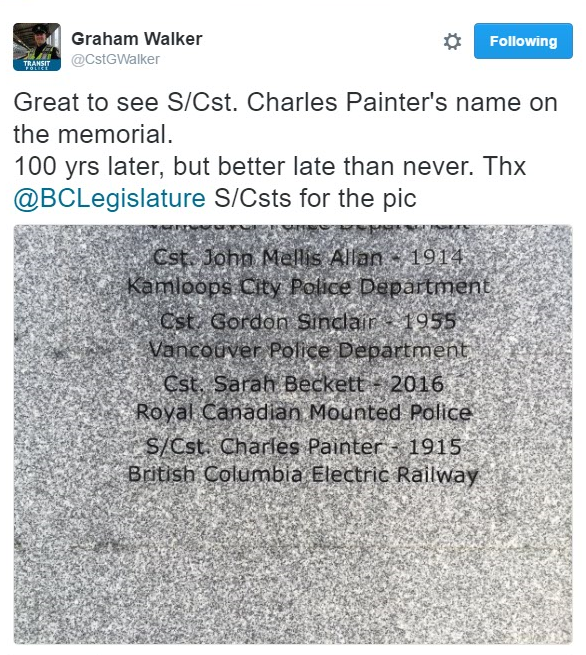

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.

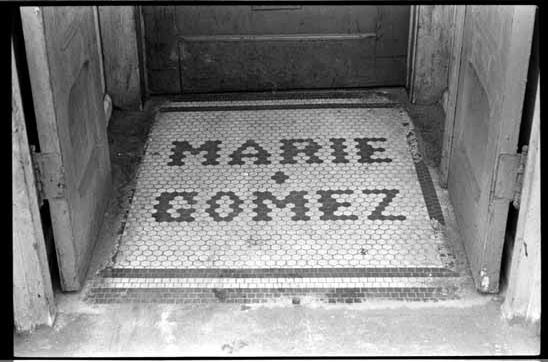

Cat has access to the Museum’s records which include arrests by the morality squad in the 1920s. She put these records to good use on the tour, finding (with some help from John Atkin), a still-standing brothel on Dupont (now Pender) once owned by Dora Reno. Dora was one of Vancouver’s earliest madams. She appears in

Cat has access to the Museum’s records which include arrests by the morality squad in the 1920s. She put these records to good use on the tour, finding (with some help from John Atkin), a still-standing brothel on Dupont (now Pender) once owned by Dora Reno. Dora was one of Vancouver’s earliest madams. She appears in