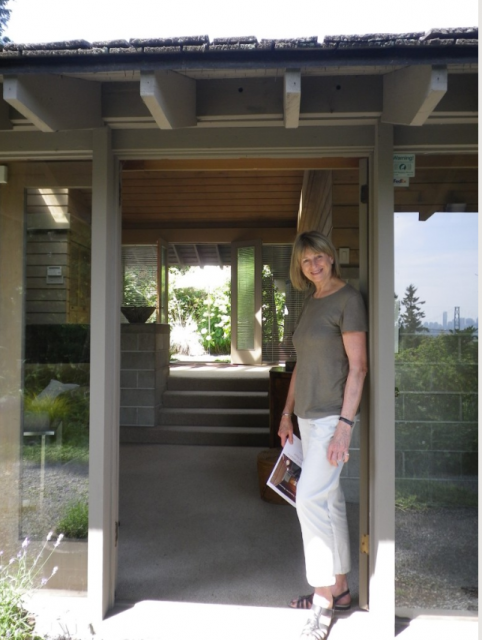

Arthur Erickson is featured in an exhibition at the West Vancouver Art Museum with photos by Selwyn Pullan

I dropped by the West Vancouver Art Museum Wednesday and joined a tour led by curator, Hilary Letwin. If you haven’t been there before, the Museum is by the Municipal Hall on 17th Street, just off Marine Drive, and housed in a funky stone house built by Gertrude Lawson in 1939.

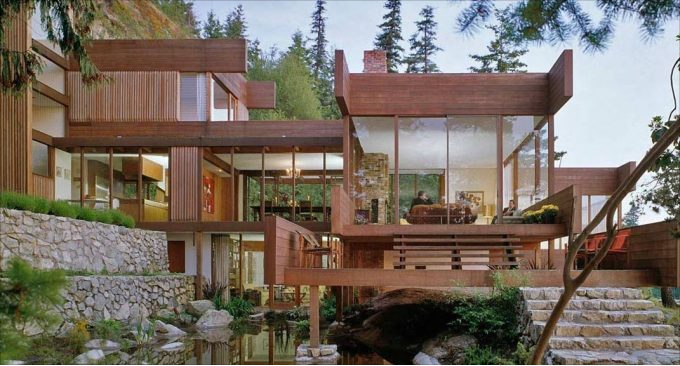

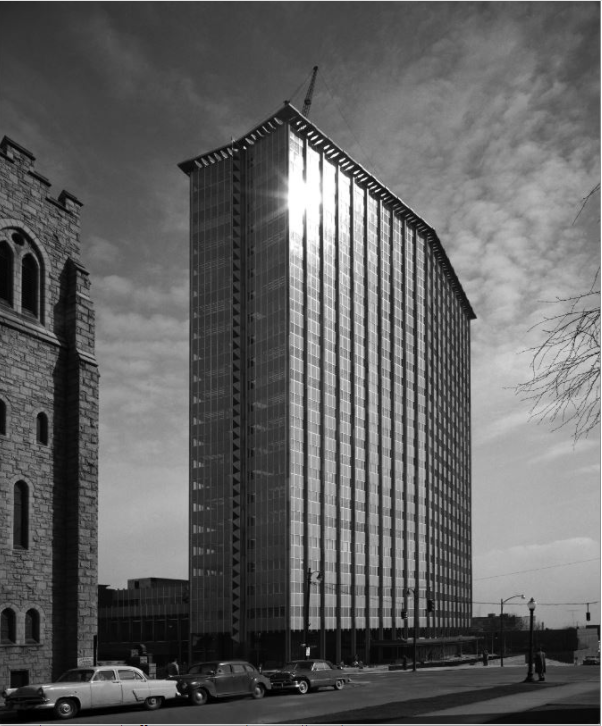

The Art Museum currently has an exhibition about architect Arthur Erickson (1924-2009). Arthur, is of course, known for buildings such as the Simon Fraser University on Burnaby Mountain, Robson Square and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC.

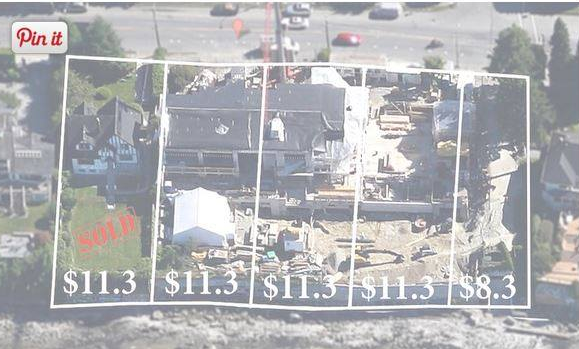

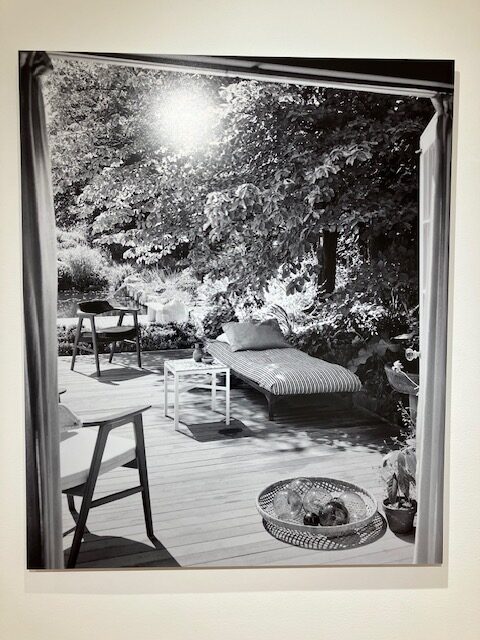

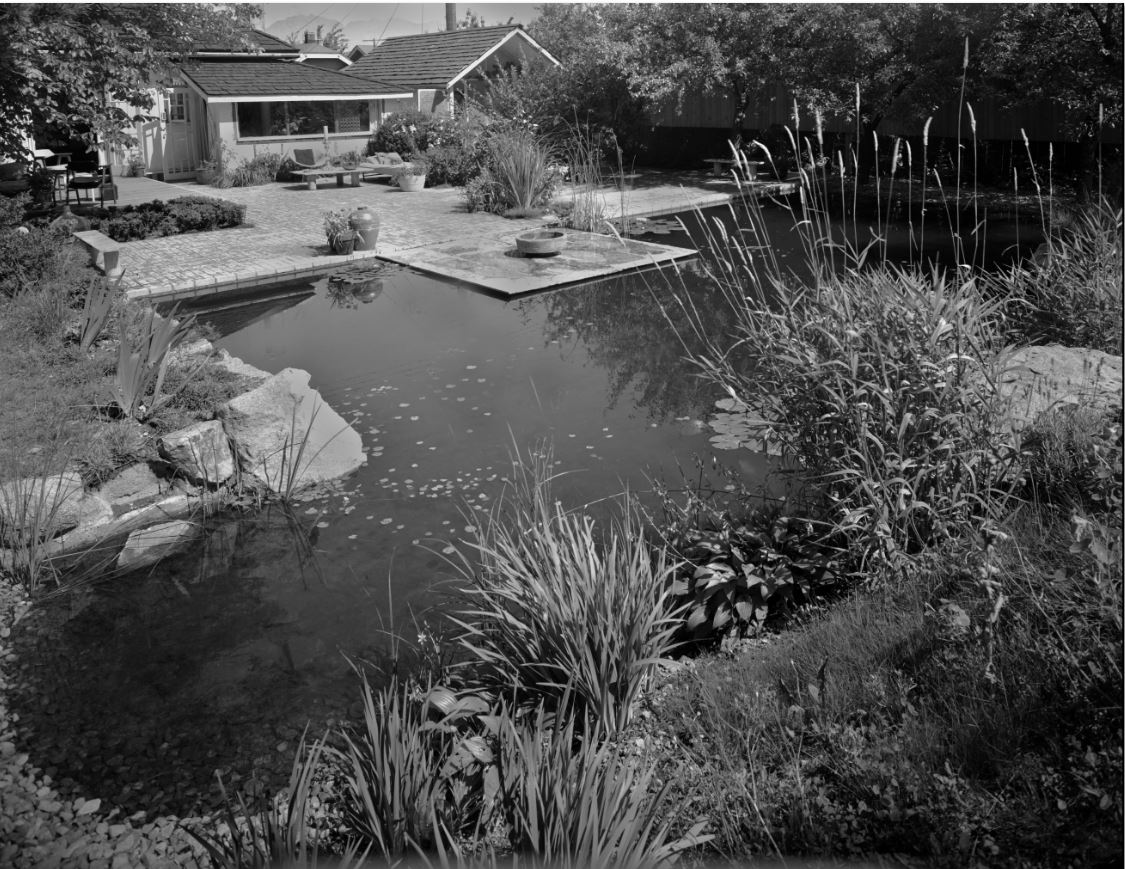

He also designed residential masterpieces like the Eppich House and the Graham House. What I’ve always found fascinating is that he chose not to design his own house but bought a large corner lot with a small cottage and a garage in Point Grey in 1957 and lived there for the next 52 years.

Selwyn Pullan:

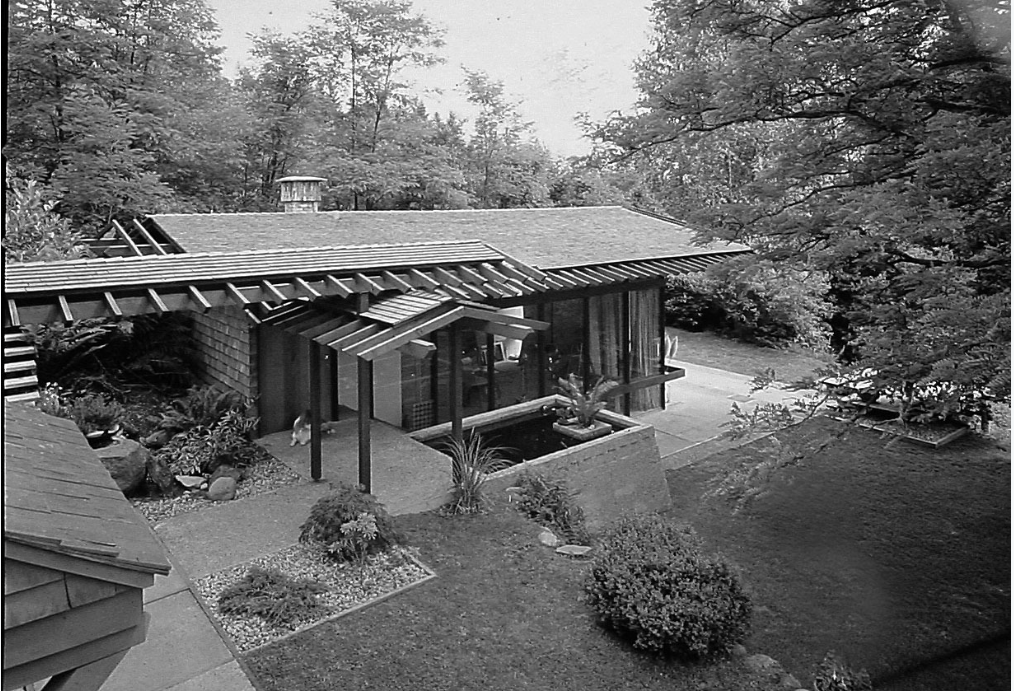

The focus of the exhibition is on some fabulous photos taken by Selwyn Pullan, a well-known architectural photographer in the 1950s and ‘60s. I got to know Selwyn Pullan, a few years before he died and spent some time in his North Vancouver home-studio, designed by Fred Hollingsworth, another North Shore superstar in the world of mid-century modern.

Selwyn kindly let me use several of his photos in my book Sensational Vancouver, but it was a different kind of experience seeing them blown up and mounted on the walls.

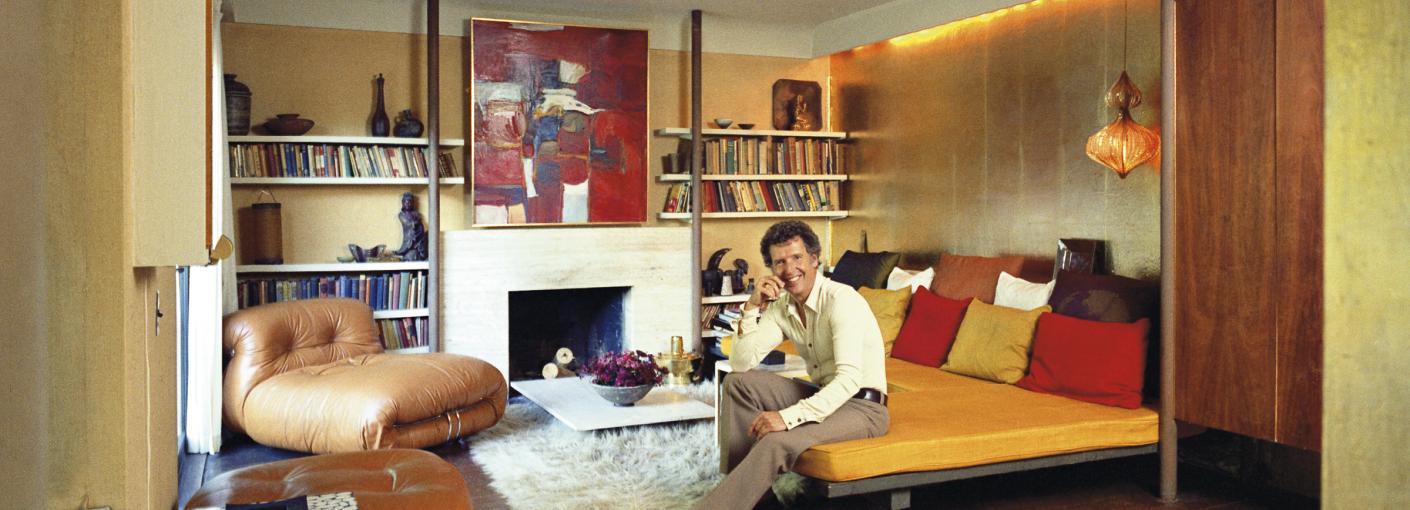

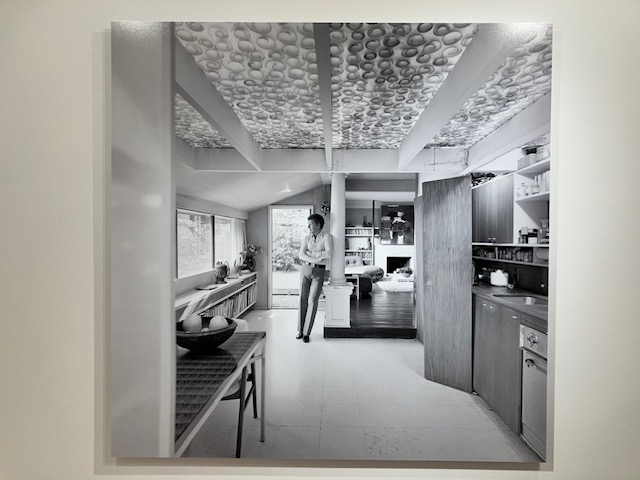

If you look closely, you can see the imperfections—dings in a corner, peeling wallpaper above a door, and some of the unusual materials that Arthur used to decorate his digs.

West Coast Modern:

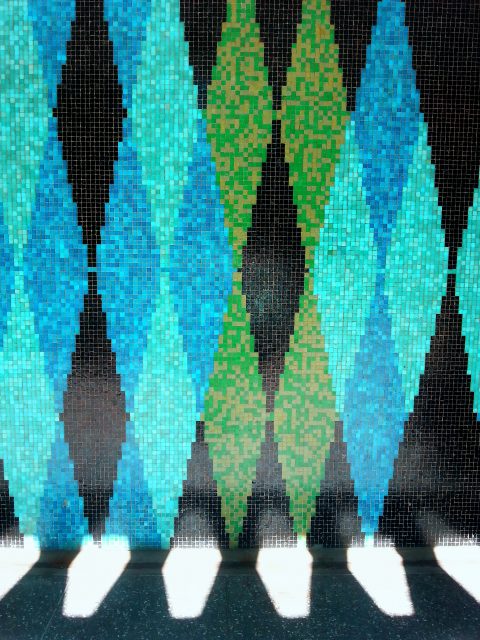

Gold wall paint eventually replaced with suede paneling, leather tiles on the bathroom wall, a ceiling made out of cedar shavings pressed between two pieces of plexi-glass.

Arthur was also big on repurposing materials.

The table he is leaning on in the photo below, is an old door. Its legs are made from concrete core.

Many of the objects he displayed have an eastern flair—a Buddha’s head, books, a garden statue. Hilary tells us that Arthur served in the second world war in the intelligence corps and spoke fluent Japanese.

A huge Gordon Smith painting that hung in Arthur’s living room is part of the exhibition. He designed two houses for the Smiths’ in West Vancouver. The second near Lighthouse Park still stands. Gordon died in 2020 at 102–one of the last of the modernist painters in Canada.

The exhibit runs until July 20 and is open Tuesday to Saturday from 11:00 to 5:00.

Arthur Erickson’s former house is owned and maintained by the Arthur Erickson Foundation.

With thanks to the Vancouver Historical Society for organizing the tour. Definitely worth the price of membership!

Related:

- Arthur’s House and Garden are on the Endangered List

- Selwyn Pullan Photography: what’s lost?

- West Coast Modern: selling architecture as art

- West Coast Modern Architecture

- West coast Modern: on display

- West coast architecture: Barry Downs

- Ned Pratt’s West Coast Modern home

- Boyd House

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.